What does democracy feel like in your body? Does it feel like anything?

Pleasant or uncomfortable? Like breathing freely, like holding your breath?

Like your house, or somebody else’s, is there room?

Does feel like shouting, or typing? Like drowning, or swimming?

Embassy

a body of diplomatic representatives; a group of people who represent their country in a foreign country.

The Embassy of the North Sea was founded in 2018 by The Parliament of Things to explore nonhuman representation, because:

We can no longer maintain the distorted dichotomy between culture and nature. We share this world with many. Law should not be centred around Men, but around Life.

The artists, designers, landscape architects, lawyers, and researchers of the Embassy share the strong conviction that the North Sea owns itself. Their work is to represent it in human arenas — courtrooms, parliaments, media. The three-part strategy: 1. listen to, 2. speak with, 3. negotiate for the North Sea. Currently, they are transitioning from the listening to the speaking phase.

Representation

This is much more than a theoretical intervention. Representation works on a lot of levels. It can be

a person or group that speaks or acts for or in support of another person or group

or

something (such as a picture or symbol) that stands for something else

It can also be

a painting, sculpture, etc., that is created to look like a particular thing or person

And finally:

the act of presenting or describing a person or thing in a particular way

There is a translation problem, of course: In order to speak on behalf of someone, it is important to understand the other’s point of view. Nonhumans do not communicate the same way we do, using a symbolic language system. But there are other ways of knowing and sharing knowledge. The North Sea exists in the same sensory world as we do. We can feel it, see, hear, smell, taste, touch it. Meaningful representation has to be immersive, aesthetic, playful, multi-sensory, which is why the Embassy works with sound artists, food artists, costume designers.

How do you portray something as immense as an ocean? How do you listen to its interests? Who has access to the spaces where the fate of oceans are decided? Who gets to speak? And who is the listener?

Assembly

a company of persons gathered for deliberation and legislation, worship, or entertainment

On the 31st of January, the Embassy of the North Sea hosted such a company of persons at Theater de Regentes in The Hague. We gathered in order to deliberate on behalf of three ocean-dwelling entities: The seagull, the jellyfish, and the polymetallic nodule. The object of deliberation: the United Nation’s Ocean Conference declaration, a non-binding agreement formulated in 2022. How do the words of this declaration — diplomatic, formal and formulaic— need to be edited, changed, discarded, rearranged, in order to truly represent the interests of the ocean’s seagulls, jellyfish and deep sea metallic nodules?

We had been instructed to dress the part, all blues and blacks and bluish greens. The Embassy’s artistic director Harpo ‘t Hart reminded the packed auditorium: “You are not a seagull, nor are you a jellyfish or a polymetallic nodule. It also isn’t very likely that you'll ever become or know exactly what it's like to be one of them. But that should never stop you from speculating and imagining. Because we share a world with them, and therefore we have to care.”

Caring comes with shaking off uncaring traditions, questioning both content and form of political assemblies. Black suits and ties won’t do it anymore. What if everybody gets to speak? And everybody is the listener?

I decided to join the polymetallic nodules working group and immerse myself in the lightless world of the ocean floor.

polymetallic nodules, also called manganese nodules, are spherical precipitates of manganese, iron oxides and other metals (e.g., copper, cobalt, and zinc) that form on the ocean floor around a core material, such as a shell fragment or shark's tooth.

Social scientist/cultural theorist Dr. Magdalena Gorska and marine biologist Dr. Sabine Gollner transported us into the depths: “We all know we live on a blue planet. 70% of the earth is water. But actually, it’s a black planet. Light only penetrates 200 metres downwards through the water, so 90% of all ocean is dark.”

The nodules are found almost 4 kilometres down, lined up on the ocean floor. What do we know about that environment? What are we able to see, through technology, and what do those images from cameras on submersibles really tell us? How is our knowledge shaped and limited by our assumptions about the world?, the researchers asked.

Accumulating metals from the water, the nodules’ growth rate is a glacial few millimetres per million years. Begging the urgent question: “What do we learn from the contrast of the slow time of the nodule and the fast time of extractivist capitalism?”

The nodules share this landscape — fine, muddy sediment — with a wide variety of other beings, most of which still uncatalogued by humans, although 5000 of them have been “discovered” in the past five years alone. Fish, anemones, octopuses and sea cucumbers spend their perpetually nightly lives on and around the nodule fields. Even the nodules’ smallest cracks and crevices are alive with organisms ranging from tiny to microscopic: “What do we learn from the nodule about relationality?”

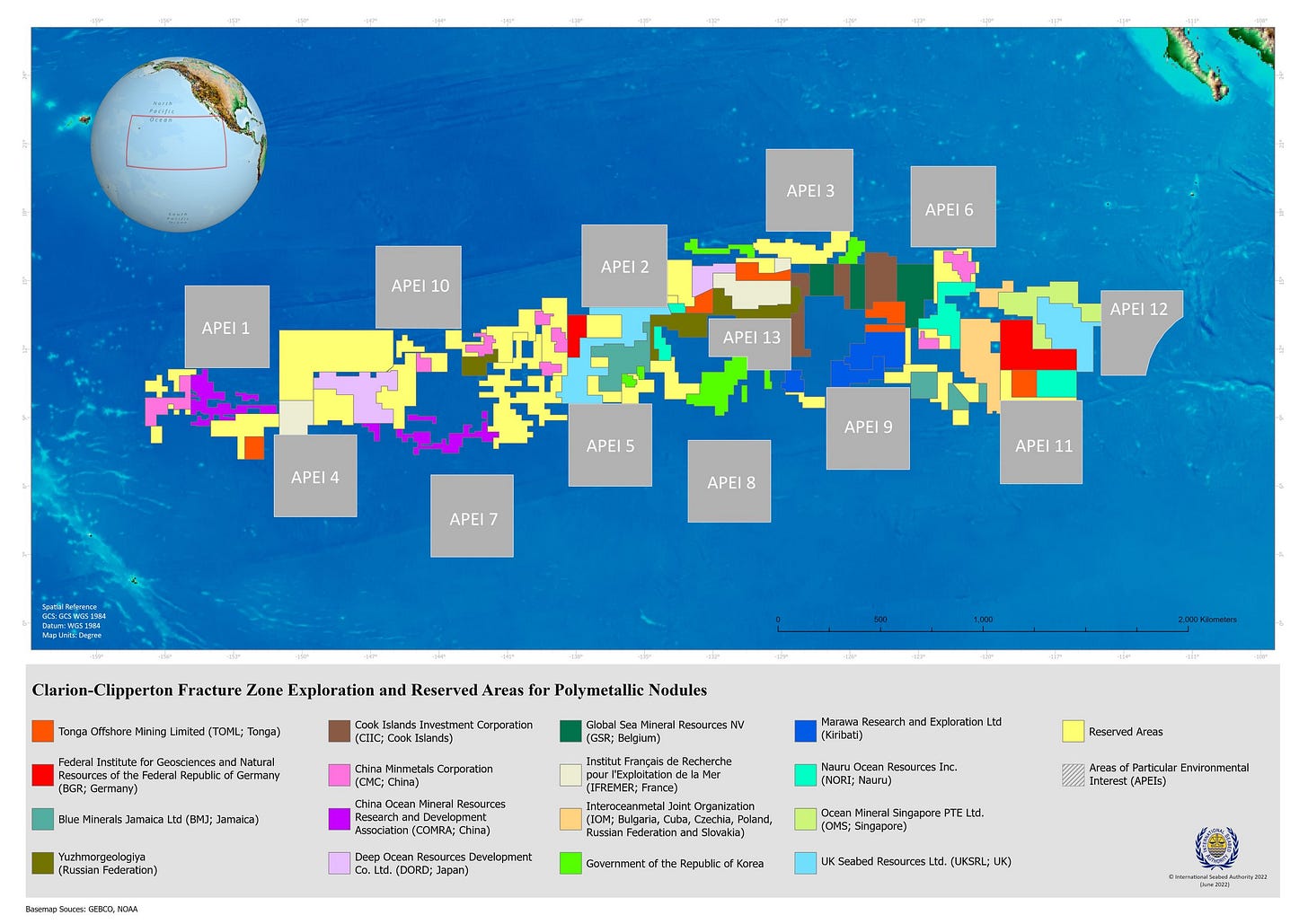

Human contact with polymetallic nodules is concentrated on the Clarion-Clipperton Fracture Zone, an area in the Pacific ocean where a number of countries explore possibilities for deep sea mining under the governance of the International Seabed Authority. Comprised of 117 member states and responsible for 54% of the world’s oceans, the ISA is tasked with the dual mandate of “organising and controlling all mineral resource activities in the area for the benefit of humankind as a whole”, as well as ensuring effective protection of the natural environment.

There is no commercial exploitation of polymetallic nodules yet — the ISA has been working on a set of regulations since 2011. However, it is technically possible to mine them, and many contractors are impatient to get started.

What colonial and trade routes have been taking place in the nodule's waters? How do pollution and global warming resonate in the nodule's atmosphere? Who make the decisions? Who make profit? What histories of privilege do they carry? What allows them, us, to think we have the right to extract the nodule's existence, to interfere in that ecosystem?

Consensus

general agreement; unanimity; group solidarity in sentiment and belief.

After a coffee break, mystified by the strange presence of slow-meandering seaweed-monsters through the crowd, the polymetallic nodule working group gathered underground, in a white-tiled former swimming pool.

It was then that I started feeling democracy in my body. It felt like a state of high-alert, enhanced listening. Preparing for the possibility of speaking up inside a room full of people. “Your voice really counts and I really hope you will all participate as actively as possible”, the moderator Carolijn Terwindt, dressed from head to toe in a polymetallic nodule costume, began. “I hope you all feel very comfortable. If not, please do something about that.”

Speaking up inside a room full of people is an untrained muscle for me, or rather, a muscle inhibited by all manner of anxieties. It’s profoundly different from dropping an envelope in the mailbox, that other, privileged, safe and removed contact point with democracy.

Declaration

something that is declared: made known formally, officially, or explicitly; a document containing such a declaration; a statement made by a party to a legal transaction usually not under oath.

Our task, as a working group, was to re-write the 10th paragraph of the UNOC declaration. I’ll paste it here for you:

We emphasize that our actions to implement Goal 14 should be in accordance with, reinforce and not duplicate or undermine existing legal instruments, arrangements, processes, mechanisms or entities. We affirm the need to enhance the conservation and sustainable use of oceans and their resources by implementing international law as reflected in the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, which provides the legal framework for the conservation and sustainable use of oceans and their resources, as recalled in paragraph 158 of The Future We Want. We note that this year marks the 40th Anniversary of the adoption of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea.

Now let go of your concerns about anthropomorphism for just a moment and imagine you are a polymetallic nodule on the ocean floor, snug under a weighted blanket of four thousand meters of water. You are ten million years old. 10 x 50.000 human generations. The center of you is the tooth of a prehistoric shark. It was once used to bite into swimming creatures that have long since changed beyond recognition. At that time, the boundary between humans and chimpanzees was still more than blurry, too. Your world is lightless but not lifeless, not at all. You’re a dependable, indispensable host for so much scurrying activity. In your shark-tooth core, you know you’re very close to forever.

Feel free to substitute your own imagination for mine there. I’m curious about how we all fall short in different ways. Then consider the words “undermine”, and “sustainable use of oceans and their resources” once more. What do they mean? What do they need to change into?

Negotiation

conferring with another so as to arrive at the settlement of some matter.

Back in the former swimming pool in the basement of a theatre in The Hague, professors, researchers, lawyers, activists, artists, design students, and writers are lined up like nodules on the ocean floor. Anyone can raise their hand, ask a question, raise a concern, formulate a proposal. On every proposal, everyone gets to vote. If the vote is unanimous, the proposal is adopted. If it isn’t, opposing voices get to speak, and a new proposal is negotiated. This means, your voice holds sway. Your voice can veto. Use it conscientiously. The process is repeated until consensus is reached. Adopted edits are written into the text in real time.

So far, so good. Before negotiating the text, however, we interrogated process, genre and language.

“Do we have to rewrite these texts, or should we just write a new text?”, someone inquired. “It's up to you”, the moderator responded. “Not just you. It's up to this delegation.”

— “I'm just wondering what kind of language is allowed in this text, and what kind of words can be used.”

— “It's all up to you. It's a text. I do want us to take it seriously as something that can be taken to the UN meeting, and that it would become a part of this Ocean Declaration.”

The nodules’ timeframe, the strange — to us — nature of their existence scrapes at the limits of language and crashes like a wave against the cliffs of formal, measured, institutional wordings and phrasings of the UN declaration.

Who are we writing for, again? The nodule, which demands something entirely different from us? Or the UN Ocean Conference, which expects, respects, or dismisses certain kinds of language? Or the nodule, but by way of adjusting to the ocean conference?

Which kind of text will be heard, which drowned out, undermined?

We put the notion of writing a radically new text up for a vote. No consensus. I’m going to let you listen into the room:

— “Write a new text but keep elements of the old, so it’s comprehensible for them. Use the structure as building blocks.”

— “I would say that in some way it has to resonate. If you want to present at this conference, then it has to somehow connect. I agree with the previous speaker.”

— “I think when you communicate, you should always think who your audience is. And in this case, if it's going to be the UN member states, we need to take that into account. Writing something abstract would be nice. It might be touching, but I think it's difficult to make it applicable to change in the real world. We need to be pragmatic.”

On the other hand —

— “I would actually like a new text that may be as radical or out of tune as a manifesto or a poem, because I have the feeling that you have to shake to be heard. And if it's too much in the language of policy makers…the words are so vague. Chewing on a sentence like that, comprehending it, I think the meaning beyond it dissolves. And by writing in a different tone, it will be heard. It will not be taken up. It will not be immediately copy-pasted into an official document. But I think it will create way more of an earth shake inside of the people whose job is to work on this than if you're trying to use their words and get lost in the nuance.”

— “I recognise that we can sometimes be in a bit of a crisis of imagination, and especially people who work on these documents as well. So I think we need to allow ourselves to dream a bit bigger and allow the space for new things to be accepted. We're closing possible futures out because we're not allowing ourselves to incorporate them in the now.”

— “It's really important to take into account that whatever comes out of this is not only non-binding, but also in whose interests the UN are acting and will continue to act no matter what we write. So basically, no matter how inspirational our language is, there is no language in the world inspirational or powerful enough to make the UN act against its own interests. And the interests of the UN are not necessarily dominated by states, because that's not what it is. It's by companies who want to mine. So basically, if anybody in this room thinks that us sitting here together coming up with a great text will change the interests of capital, I'm sorry to disappoint you, that will not happen. The UN must be abolished if we're going to undermine, but that's not something we can do with a text. So now the choice that we have is either we acknowledge the context in which this is happening and we choose a radically different form of language to kind of shake them up in that moment, or we continue to continue in this language.”

— “I'm just trying to imagine the UN Ocean Conference as I know them. How are we going to deliver the text? If it's really to shake things up, then yes to this proposal, but if it's to sit down with the member states and encourage them to recognise the text, the modified proposal, so they can follow what we're saying as on behalf of polymetallic nodules and how that fits in with what they've already drafted, it’s a different question. To me, that's just unclear. I don't know how to vote.”

— “I think it's a matter of creating a critical mass. That takes time. But the fact that we are here having a discussion with the vocabulary that we are using now, this would have been totally unthinkable 15 years ago. Only 15 years ago. So we have gone a real stretch already. I'm not going into their reasoning and into their vocabulary. I'm convinced that another way exists, and it's slipping in, it's coming. It's still marginal. I'm very aware of that. But it sounds to me like we're using the word inspiring as something that can’t be taken seriously, and I find that concerning.”

— “Can I just suggest something? I feel like we're in a situation where we have two strategies. One is working with the language and with the institution. One is refusing working with the language and the institution. How about we write two proposals instead of one? We talk about plural vocabulary, let's have plural vocabulary.”

We put this proposal up for a vote. No objections.

The completely different text

It is not easy to write a completely different text. Someone proposed using ChatGPT; was quickly overruled. Again, we ran up against the limitations of language, or rather, the limitations of English, our lingua franca.

— “English is written in 70% nouns, and does not recognize mountains, rocks, and rivers as living entities, whereas other knowledge systems do. So we should emphasize the intrinsic value of things and the limitations of our language.”

Someone else suggested to include the “canoe protocol”, an Indigenous concept whereby strangers approaching by canoe must introduce themselves, state their intentions honestly, ask for permission, and only then step ashore. (And only then descend into the depths to scoop up the ancient minerals. What does “permission” mean, then?)

Another member of the delegation emphasised gratitude: “Maybe we can just have some gratitude towards it. Like wow, look at this incredible thing. We know it is on our planet, and that it is hosting our kin at the bottom of the ocean and doing a brilliant job of it.”

Others insisted on incorporating the nodules’ timescale. How do our lifespans compare to theirs? One aspect of it is performance:

— “This whole conversation, it's been like, how do you vote? How do you vote? Yes, no, yes, no. But I'm a super slow thinker. I might decide tomorrow how I wanted to vote on something we discussed today. So, one way of feeling that rhythm of different ways of being in time could be that the text is instructed to be read very slowly. That you have to wait to hear it.”

— “They are ancient, right? They are old, they represent wisdom, they represent something way bigger than our very temporary existence on the planet. The rights of the elders, we should be respecting that.”

I raised my hand, spoke up inside the room full of people to say what I’d been meaning to say: “I think we're writing a deep time speculative fiction. It's not just seven generations into the future, but 7,000 or something. Life can be organised completely differently, the UN most likely doesn't exist, and it's really up to us what we can imagine for human life to be then, if it still exists.”

What I meant is, nodules help us think far beyond our present moment in all directions. This diffuses current conventions of genre completely. It reminds me of the linguistic efforts for communicating across deep time in the field of nuclear semiotics, long-term nuclear waste warning messages. They are symbols meant to resonate with humans 10.000 years or so from now emphatically enough to deter them from exploring or drilling at nuclear waste sites.

The symbols are meant to convey, among other things:

Sending this message was important to us. We considered ourselves to be a powerful culture.

This place is not a place of honor... no highly esteemed deed is commemorated here... nothing valued is here.

The danger is still present, in your time, as it was in ours

How would we tell far future generations about polymetallic nodules, on roughly the same scale of linguistic abstraction as telling them about nuclear danger? How do we enact a more hopeful message in a bottle?

Sending this message was important to us. We considered ourselves to be a powerful but destructive culture. Do not come near. This is a place of great honour. It is where we decided to stop.

Others in the room were thinking pragmatically.

— “So we'll say first, this is the problem: the problem is Western capitalist extractivism, which is creating these conditions. And then we want to emphasize the right to live of the whole planetary ecosystem, not just humans.”

— “We write that we take responsibility for the harm we’ve done. The state the Ocean and its inhabitants are in today is because of us. Let’s mention that legal policy has failed, it's been a lot of talk, usually at UN conventions, and not a lot of action. Talk about the living and non-living entities or residents of the Ocean. And emphasize preventing harm. In legal terms we talk about the precautionary principle, which hasn't been applied very well, but it basically means if you don't know what the impacts are, you don't do it. And when you're talking about the deep sea, we talk a lot about a moratorium. A total ban is complicated, but a moratorium is possible.”

Moratorium: an agreed delay or suspension of activity.

If you are in consensus with the idea of a moratorium on deep sea mining, consider signing this petition.

The edited text

With only ten minutes of the negotiation our remaining, we resolved to let all suggestions stand as suggestions and returned to the version of the text which retains the structure and elements of the original document.

— “I'd like to propose deleting, “we affirm the need to enhance the conservation and sustainable use of oceans and their resources”, and inserting, “we reject the outdated assumption that the oceans and their contents are just resources to be use”.

— “To keep the spirit of the symposium, can we stick to Ocean?”

— “I accept this friendly amendment.”

However, the proposal got hung up on another question of terminology, one that comes up again and again and again when people try to talk about anyone or anything other than ourselves. What do we substitute for “resources”?

— “Instead of residents, shall we say entities both living and nonliving?”

— “I object to the word non-living. Everything is living.”

— “Would it be an idea to just state that residents include entities like polymetallic nodules?”

Contents of the ocean? Just ‘entities’? More-than-human entities? Inhabitants and materials? Residents and materials? Residents and habitats? Biotic and abiotic ecosystems? All forms of existence?

No consensus. Due to time pressure, we agreed to let the contentious term stand in brackets: “We reject the outdated assumption that the Ocean and its [inhabitants] are just resources to be used”.

— “Who is in favour of this proposal?”

— “Maybe you can drop the word ‘outdated’.”

— “So, when the word outdated is dropped and the sentence reads, “We reject the assumption that the ocean and [its inhabitants] are just resources to be used”. Who is in favor of adopting this sentence into the text?”

Consensus. And time up.

And onwards, like swimming.

Addendum: The Forbidden Madeleine

Despite best efforts at playful and multi-sensory representation, some artificial boundaries remained intact: Sourcing salt from the North Sea, artist Sheng-Wen Lo had baked madeleines and other small cakes for the delegation to taste during the break and after the assembly. The theatre’s regulations did not allow for these risky baked goods to be consumed inside its premises. We were only permitted gazing at the ocean-infused madeleines from afar. It was not deemed safe to let the ocean circulate through our bodies.

Further Reading:

The Embassy’s Non-Human Library

Introduction into Latour’s theories of governance for the nonhuman by The Parliament of Things

If you read Dutch: In Gesprek met de Zee by Arita Baaijens (whom I met at the assembly!)

Recent interview with three embassy representatives on moving from the “Listening” to the “Speaking” phase