Sharing a city with countless living nonhuman beings isn’t complicated enough, so I want to draw your attention to the fact that we also currently share the same city with animals that have gone extinct.

The exhibition The Call of the O’o at the Allard Pierson Museum, on until the 26th of January, begins from the vantage point of extinction — the ghostly recording of a male Kauai O’o (Hawaa’ian songbird)’s unanswered mating call — to subsequently “shed light on the relationship between the people of western Europe and nature, from the sixteenth to the nineteenth century.”

The title is a pun, strangely enough: “When you think of the state of the natural world today, you likely think: Uh-oh.”

They write:

“Wonderful drawings, books and prints illustrate how western Europeans have studied and depicted nature, and what their motives and values were. An inquisitive mind and a sense of wonder went hand in hand with hunting, overexploitation and destruction of habitats. Why did humans view themselves as standing outside of nature for centuries?”1

Among those who have made their way into Amsterdam for this exhibition are a taxidermied O’o, great auk (flightless bird from the North Atlantic) and quagga (Southernmost ecotype of the zebra, endemic to South Africa). For this particular quagga, the journey was a return: she lived for sixteen years in the Artis zoo, and when she died there in August of 1883, nobody was aware that she had been the last of her kind. Now, 140 years later, she stands in a glass case less than two kilometres away from her former enclosure.

Caption: Quagga at the Allard Pierson Museum, play to hear the call of the O’o. Video by Or Schaap.

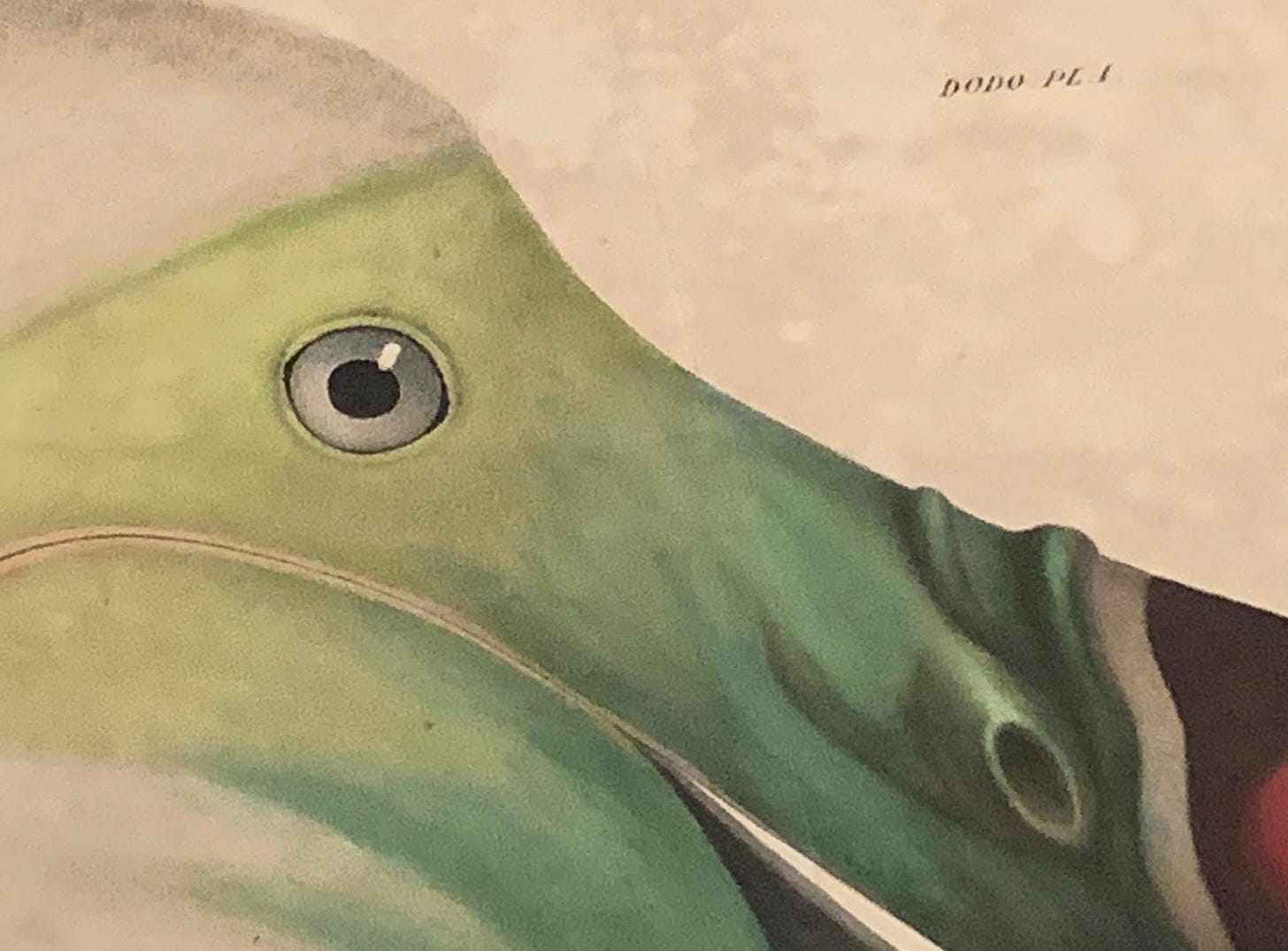

The title of this room is “Disappeared”. It follows a series of rooms titled Collected, Named, Changing, and Interwoven. “Changing” represents the 19th century’s theories of evolution, and “Interwoven” the rather recent admission of western Europeans that all life is interconnected and mutually dependent. Including our very bodies, our selves, and wait, how precious it all is! And then, circle back to the uh-oh, we find ourselves in the midst of mass extinction. Cue panicked eye of the dodo —

But the great auk, O’o, and quagga aren’t “Disappeared”, not fully — they’re here in the room with us, after all. Far from their native coasts, forests and grasslands, they still share our city. Only dead, behind glass, exhibited in all their ancient unchanging accusatory animal-object ambivalence. “Why did humans view themselves as standing outside of nature for centuries?”, you can hear the quagga scoff if you place your ear close enough to the glass — “Well, where do you think you’re standing now, and where am I standing?”

Less than two kilometres away from a zebra suspended in formaldehyde at the Stedelijk Museum for contemporary art. The zebra-cube, titled The Incredible Journey, is part of famous British artist Damien Hirst’s Natural History series of animal corpses — cows, a lamb, a shark — displayed in this “aesthetically slick and clinically immaculate” way. Hirst is spurred by precisely the same motivations as those historical western Europeans the Allard Pierson museum tries to problematise: “understand the world by taking things out of the world… you kill things to look at them”. Much like the final pair of great auks were killed on commission for a merchant who wanted specimen. It’s the polar opposite of “Interwoven”, and out of it come wonderful drawings, books and prints and glass cubes with animals inside them. Say you visit both museums in one day, you’d stand outside a glass case examining a dead animal of the genus Equus twice.

Only in one case, it’s an artwork priced close to a million British pounds and in the other, a collection item meant to inspire care about species extinction and re-evaluate our relationship with nature. “I couldn’t say what I wanted with a painting or with a photograph of an object”, Hirst has said — “I wanted the real thing”. The same, in a way, goes for the Allard Pierson museum. And to what end? “I want to give you the energy to go away and think about your life again”.2

In the case of the Allard Pierson Museum, there seems to be a strange dynamic at work in which curatorial choices both problematise and affirm the destructive western European “outside of nature” fallacy at the very same time. I must admit that I enjoyed walking through the exhibition, enjoyed looking at the wonderful drawings, books and prints, felt my inquisitive mind and sense of wonder reflected in them. I nodded at the curatorial texts about how these drawings, books and prints are inseparable from histories of Dutch colonialism and felt somewhat haunted by the recording of the O’o but didn’t, to be perfectly honest, pay much mind to the presence of the actual 156-year-old quagga in the room.

How would we curate an exhibition on extinction that actually makes us think about our lives again, an exhibition that displaces us, knocks us clear off the western European spectator’s taken-for-granted outside-the-glass pedestal?

I say: let the horse girls do it.3

In the Routledge Handbook for Human-Animal studies, the artist and writer Steve Baker addresses the issue of the dead animal in art:

What is called for in these circumstances […] is a language that is somehow closer to its objects, enlivened by its objects: its dead objects. This would be a form of language that is not averse to handling its objects – handling them with writing, in a manner no less fleshy and familiar, and no less careful and attentive, than other forms of handling museum exhibits and artworks. (Or, indeed, of handling living creatures.)4

I haven’t touched a quagga, obviously, nor any zebra. But I have touched a horse. For a few of my teenage years, I cared for a white mare called Frosja: I would visit her multiple times a week, scrape dirt out of her hoofs and scrub them with apple cider vinegar to prevent fungus from growing in them, brush and occasionally braid her hair, stand at her side holding a carrot such that she had to stretch her neck therapeutically to reach it, evade in a practiced manner when she snapped at me while I tightened the saddle around her belly, flex and release my fingers around the reins connected directly to a piece of metal inside her mouth, struggle to convince her to move on from patches of sweet green grass on our walks. We were integral parts of each others’ lives: I kept her and loved her and handled her and learned from her, and she carried me and snapped at me and let me stroke the soft hair on her forehead.

Here’s what I mean: Words have the power to take us much deeper into the lives of the animals we now only see in glass cases, beyond their present object-quality and into the realities of what mattered to them. What they ate, what it tasted like, where they slept, how it felt on their skin, how they raised their young, what sounds they used to communicate, and what it was like to interact with them, as humans, what stories were told about them in the voices of those who actually shared interwoven lives with them for thousands of years.

If we’re doing it here, from the point of view of western Europeans, then let the horse girls do it, as almost-hybrids attuned to the faintest signals in the others’ physicality. I don’t mean for them to braid the quagga’s hair — I want them to comb through her fleshy and familiar stories. Let them do it in collaboration with Indigenous artists and together they’ll know the words. Let them attend to the aliveness-that-was: notice the beige hair on her flank, reach our hand through the glass and place it there lightly, feel her skin twitch then relax, warm and soft and moving steadily with breath — or the deadness-of-now: the cold and unresponsive skin, the expressionless glass eyes, the seams on her chest. Or in hard-mode: both at the same time. Let them curate a room that doesn’t allow you to forget that extinction isn’t aesthetically slick and clinically immaculate. It’s blood seeping into grassland and flies that land on your arm after they’ve fed on a dead quagga because there are no glass cases. It’s a mess, it’s unclenching your fingers to drop the gun you were holding and your fingers melting and solidifying into hoofs, and it’s the horse girls rinsing them with apple cider vinegar.

All quotes in this paragraph are from https://www.sothebys.com/en/buy/auction/2021/evening-sale/the-incredible-journey

You may read “horse girls” as a generic term for anyone who has lived in intimate proximity with an animal for a prolonged period of time.