In September 2024, I attended Placemaking Week Europe and participated in workshops around speculative design, world building, and libraries situated in and around a newly realised tidal park in Rotterdam.

Through these workshops, the park opened up like a collection of speculative short stories, each page a different future. In conversation with strangers, with our shoes off, what else can we imagine the city becoming?

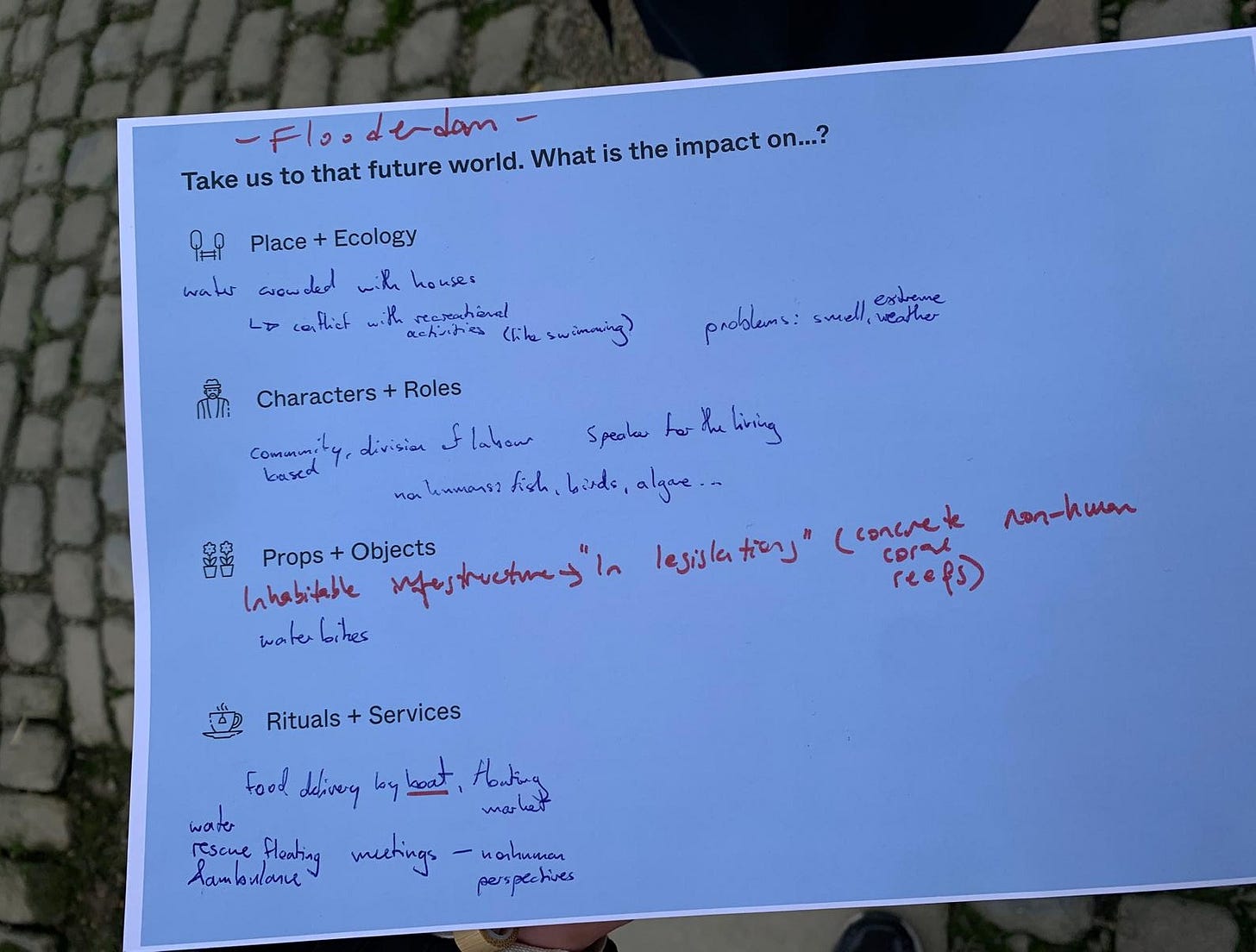

Rotterdam, 2050. It’s a warm but overcast autumn afternoon. The former tidal park Keilehaven has become one of the most sought-after new neighbourhoods of “Floaterdam”, an aquatic settlement constructed in the wake of the previous decades’ housing market collapse. The water crowded with houses and people, there is little space for recreational swimming, and attempts at sunbathing during the hot summer months are often soured by the odours emerging from the densely populated canal waters. Nevertheless, Floaterdam’s community is tight-knit: every other week, a rotation of representative residents mount their water bikes and gather to discuss the latest flood damage or reported cases of illegal fishing in the public arena of the floating library. A designated speaker for the living advocates for nonhuman concerns, and a librarian acts as mediator while representatives pass around bags of algae crisps.

Grounding the Future in Place

Placemaking is always, in one way or another, about design — not only that of objects like the prototypical bench, but also of the interactions, relationships, and rituals that define a place. Design, in turn, is always about the future. “The future emerges directly from the objects we design”, notes philosopher Timothy Morton.1 Futures emerge from the bench, the bike path, the cars, as well as the interactions, the relationships, the rituals — the sitting and chatting, the cycling, the driving and listening to the radio and stopping for gas.

Back in the Rotterdam of 2024, Rosanna Vitiello from The Place Bureau and Gemma Jones from the School of Critical Design explain that they approach the responsibility of the designer deliberately, with playful seriousness. “When you try to design a place, very often you realise that you’re working with a very long time frame. It's going to take years”, Rosanna tells us. This is why The Place Bureau joined forces with Gemma, who specialises in 'future visioning and cultural insight. Together, they developed a toolkit for imagining place futures. It helps place makers apply the abstract concept of speculative design to the rooted realities of their specific environments: “We try to get people to feel what it might be like to live in that future, and then take a step back and go: Okay, did I like that feeling or not?”

Through this method of “rapid prototyping” possible futures, practitioners get a chance to adjust their actions — and their future-making designs — in the present moment. Taking the new tidal park as our point of departure, we were able to make five different scenarios for a 2050 tidal park come alive with characters, objects, and rituals in just over twenty minutes.

What is a Library?

Optimistically, the residents of 2050 Floaterdam regularly gather, eat snacks and practice democracy in their public library. When asked: What is a library?, I might answer: a place I can sit and write without paying for a complicated coffee; another common definition is “a place in which literary, musical, artistic, or reference materials (such as books, manuscripts, recordings, or films) are kept for use but not for sale, or a collection of such materials”.

In other words, a library is place that transports knowledge through time, for free. “Today is your lucky day, because today, you will all become librarians”, Rob Bruijnzeels from the Ministry of Imagination welcomed us earlier that day to a workshop titled Unlock the City, Discover the Library. Together with Rob, his colleague Florian de Visser and the two Icelandic librarians Dögg Sigmarsdottir and Martyna Karolina Daniel from the Reykjavik City Library, we set out to explore and catalogue.

“In a way, the whole city functions as a library, because a library is about knowledge, about stories, about meeting people…it’s so much more than just books”, they explained. While walking, we were invited to pay close attention, noting any objects, sites, smells, or sounds that might be interesting for the collection of this city-library. “Use everything for inspiration. It can be anything you find along the way. Maybe vegetables…”

Our stroll led us past the tidal park and culminated in a picnic: “If we were to design a library, we’d always put a kitchen in the middle, because that’s where the conversation starts. The party is always at its best in the kitchen”, Dögg and Martyna proposed. Their research question: “What kind of conversations do we have when we eat and sit together with strangers, without shoes on?”

Time Machine Tidal Park

Rotterdam, 2050.

“Hi, this is Rosanna Vitiello reporting live from The Place Bureau. I'm here with Amanda, who is a tourist. She recently arrived here in Rotterdam, a city that has boomed in terms of tourism in the last few years, after Amsterdam basically decided to throw everybody out. Amanda, tell us where you're from and how you got here.”

“Hi! I came here with a cruise ship. We all used to be really critical about cruise ships, but now they are my main means of transport because tourism has changed so much. You can't just go somewhere, chill out, spend your money, enjoy some good service — cruise ships now are what we used to know as container ships. And I'm working on one.”

“Right, tell me a little bit about your job on this cruise ship and what you love about it.”

“I mean, back then on the cruise ships I used to really love the huge pools and all the fancy infrastructure. Now it’s just full of containers. I'm a bit sad about it, but at the same time, we take goods around the world and we know what goods we are transporting. That awareness is a huge improvement. When we come to a new city we get to explore, but we also work on distributing the goods. I get to know many people through my holidays and work. They became the same, so I’m basically on a permanent holiday. You could call me a cruise ship nomad.”

“When you arrive here in Rotterdam, what do you do? Do you guys go swimming?”

“Yeah, I’d really love to try that. There are some canals in the centre where you can swim. But the seawater is sacred, of course. So we don't swim there.”

Building Blocks: A spaceship. Or a penguin.

What if cruise ship nomads, upon arriving in a city, were channeled through its library? Back in 2024, on a patch of grass not far from the tidal park, with our shoes off and a typical Dutch lunch spread in front of us, we discuss time travel.

“It’s so interesting to talk to people who know the city, the library and its history”, Dögg reflected. “It’s this continuation in the landscape and the institution, whether you see it or not. This used to be a harbour, this used to not be accessible to people…this is like what I love about walking around the city. When somebody tells me, this used to be something else. How can we get that into the library collection?”

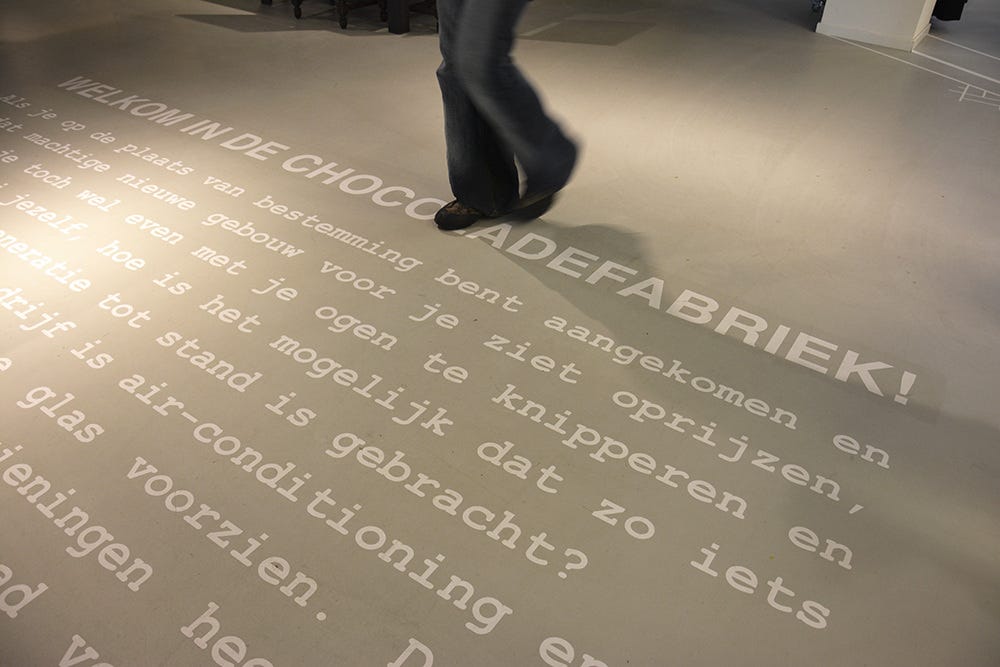

Here, Rob and Florian could speak from experience. They previously crowd-sourced knowledge in the city of Gouda, where the public library used to be a chocolate factory. “It produced chocolate until 1975 or so, which barely anyone remembers today. But we asked people in the city: What is chocolate? And we got a lot of different answers, about eating, about economy, about slavery and exploitation…” These different local imaginaries allowed librarians to bring the library’s chocolatey past into its current design. “You can build different layers of the collection and create unexpected connections. In a different city, the context would be different, of course.”

A library’s collection doesn’t need to be a stagnant wallpaper in front of which people — like me — type away on their computers. It can adapt to local pasts and current knowledges and conflicts, curated and re-shuffled to add depth and nuance to any topic of discussion. “We often compare it to playing with Lego”, the librarians added. “You’ve got the Lego bricks, and they’re the collection of the library. Now, what public libraries tend to do is build a wall. But everyone who has played with Lego knows that the fun comes from knowing you can change it anytime, make something completely different from what you did yesterday. A spaceship. Or a penguin. You can build everything with the same bricks.”

From Seedlings to Books

A good library keeps knowledge both radically accessible and safe for future generations to engage with. Rob introduced us to the Future Library, a project by the Scottish artist Katie Paterson. Consisting of a collection of unread manuscripts and a forest of seedlings, the project lives and grows in the Deichmann Bjorvika library in Oslo and the Nordmarka woodland outside the city. Every year from 2014 until 2114, a writer is selected to submit a new unpublished manuscript to the collection. Contributors so far include Margaret Atwood, David Mitchell and freshly crowned Nobel Prize winner Han Kang. Their texts are held in trust by the library and read by no one. At the same time, the seedlings outside the city grow into trees that will supply the paper on which these books will be printed when the time comes.

Ninety years from now, a new generation of people will receive the words passed secretively through time from ours. This, of course, implies a kind of optimistic trust: What will Oslo look like ninety years from now? Will there still be a library, a forest?

“The moment I eventually write the first sentence, I have to believe in the world one hundred years from now”, Han Kang writes in the essay accompanying her manuscript.

Disney World Aquatic

Rotterdam, 2050.

“I’m here in Rotterdam with Betty, who is the Aquatic Park manager. There have been terrible floods over the last few decades, but it's also opened up a whole new world for nature. Betty, tell us a bit about your job.”

“Thank you for having us today. It's a great day because the floods have been delayed, so we're not expecting another one for at least forty minutes. Don't worry, we have alerts, you’ll hear the bell. I used to work in this industrial area before it became the biggest maritime park in the entire region. Do you remember Disney World? Basically, we're the equivalent of Disney World, but for a maritime environment. We have this entire ecosystem where you can discover the underwater world. We have repurposed all the old buildings into aquariums you can access from the roof to find different species from all over the world. Let me give you some goggles — we also have kayaks, scuba diving equipment, whatever you like. This is really a place to celebrate aquatic life and also invite young people to learn more. So yeah, we're very proud of what we do.”

“You should be. And what kind of rituals have emerged in your park?”

“Oh, we have all kinds of very interesting things. We have water meditations, sometimes we have water births… but only in a special area. No swimmers around there. And regular safety trainings for flash floods… hold on, am I hearing the bell? We should probably go.”

How not to be afraid of dragons

In her essay “Why Americans are afraid of dragons”, Ursula Le Guin argues that the power of imagination is one of our most deeply human, and humane, faculties. Maturing, ideally, is not an outgrowing of these faculties but simply a growing up.

Once we realise that the future emerges directly from the objects — and the places — we make, it also becomes clear that creating futures which are significantly different from those already emergimg out of our present (infra)structures is a tricky task. This, then, is where the library comes in.

Le Guin concludes: “It is our pleasant duty, as librarians, or teachers, or parents, or writers, or simply as grownups, to encourage that faculty of imagination in our children, to encourage it to grow freely, to flourish like the green bay tree, by giving it the best, absolutely the best and purest, nourishment that it can absorb”.

In other words, our places are only as welcoming, green, playful, surprising, and challenging as we are capable of imagining them to be, and imagining something truly different takes a vivid, library-fed imagination. “By watering the saplings now – writing the manuscripts – we are tending to the future”, journalist Arifa Akbar reflects on Oslo’s Future Library. Libraries and trees, cities and children grow together, and cannot truly flourish one without the others.

Timothy Morton, Being Ecological, 76.